March 2017

I can trace back my fascination for other cultures, for anything that comes from distant lands and even for music, to a very specific time in my childhood. I was born in Sevilla, a proud, beautiful city in Southern Spain. During the times of Al-Andalus and the naissance of the Spanish empire, it played an important role as a centre of science, culture and trade, and it even was the departure point for many voyages. Now the days of glory are long gone, and it is more known for its traditions and its history, for its streets that speak of Moorish and Jewish ancestry, soaked in a hot, balmy air that smells of orange blossom.

In Sevilla you grow up surrounded by everything that foreigners expect Spain to be – flamenco, bulls, tapas. It was in the middle of all these customs that I discovered that my dreams took me far, far away. My parents used to take me to the park, and one day we saw a group of Andean musicians playing folkloric music. They were dressed in traditional attires, with ponchos and wool hats. Using traditional instruments, such as the pan flute and the panpipe, they sang songs that talked about love, melancholy and suffering, about the condor and a land so high up that it almost touches the sky. I was mesmerized, I couldn’t stop looking. Everything about them fascinated me, even the fact that they looked different than everyone around, as at the time, there were very few foreigners in Sevilla. Their music was sad but beautiful, and I just stood there, listening, letting the songs inside me, breathing their tales, learning the lyrics by heart. With my mouth open, hypnotized, until my parents dragged me home. This happened every time we saw them, and one day my parents decided to buy me their music record, my first cassette. Now I could also listen to them at home, again and again.

Years later, I have taken myself to these faraway places I dreamed of. Every trip I have done to South America has been very special, among other things, due to the complicated history between our countries, but no country has touched me more deeply than Bolivia. For the humbleness and kindness of its people, its magnificent, melancholic landscapes, its tragic history and because the Andes remind me of my childhood and finding beauty in things that come from a distant land.

I travelled there with my friend Guille, whom I have known since my family moved to Barcelona just before I turned 6 years old. Our lives seem to keep intersecting. We went to the same school and the same university, and then we both moved to London to start our careers. I left the UK to do my MBA at INSEAD, and just when I finished, he left to travel around South America, and that is where our paths would intersect again. We agreed I would join him in Santiago de Chile, and from there we would travel to the Atacama desert, cross into Bolivia, and then Peru. I would fly back home from Lima and Guille would continue his journey up north.

Part 1 – Chile

The flight from Barcelona to Santiago is a long one, 15 hours. I wake up an hour before we land, just in time to see the landscape below. Nothing for miles and miles on end. A lunar landscape of barren mountains. I have never seen anything like this before, and it’s a taste of things to come, as this trip will take me to some of the most incredible landscapes I have ever seen.

I have purposely chosen to start my trip in Santiago as I have lots of people here I want to meet – Martín, a close friend and flat mate from INSEAD, my cousin Fermín and his girlfriend, now wife, Viviana, and my cousin in law, Miguel. These first days in the city are a chance to catch up with people, recover from the jet lag, and we even have time for a quick weekend visit to Valparaiso and Viña del Mar. We enjoy the quietness and predictability of Santiago, knowing a long, exciting journey awaits us. We are a bit nervous, not sure what to expect from the next days, and feel our adventure commences the moment we start taking altitude sickness pills. Most of the trip will be at very high altitude through the Andes, and both Guille and I grew up by the sea, so we feel like fish out of water when we go very high up.

We land in Calama, the closest airport to San Pedro de Atacama, late afternoon. We have booked a guide for the next days, Zahel, who comes very highly recommended and will be showing us the main sights in the area, before we cross into Bolivia. We will be meeting him the following day, and he has sent a driver to pick us up.

The drive from the airport to the town already feels like landing in another planet. Barren land, dark volcanoes and endless, salt covered desert. Before we arrive to our accommodation, he stops in the salt flats of Valle de la Luna (moon valley) so we can take in the sights. We walk for a bit and cannot feel the altitude yet (2,400m over sea level). Instead, our breath is taken away by the land, the miles of nothing, and mountains that look like amphitheatres. The air feels dry (Atacama is the driest place on earth), and I am grateful that, despite our backpacking attitude/ luggage, I have brought a wide selection of moisturising skin care products, much to Guille’s chagrin My (very disciplined) 10 step skin care routine is a regular joke amongst all the friends who travel with me – my Korean products have journeyed to the most remote, isolated places on earth (I buy most of my products from TONIC15, while in Europe, Yesstyle and Tokopedia in South East Asia and Glow Theory in South Africa).

We are staying at Atacama Loft, in the outskirts of town. It is my first ‘glamping’ experience, and we will be sleeping in fancy tents, with a very comfortable bed inside. At night, we see the clear sky and thousands of stars – Atacama has the clearest skies on earth, for which it has been chosen as the location of a multi-country astronomic observatory, home of some of the largest telescopes on earth.

In the morning, after cooking our own breakfast, we are ready to go. Zahel picks us up in a jeep to take us to the Lagunas Altiplánicas (highland lagoons), going up to 4,000m over sea level. Zahel is really knowledgeable and friendly and very soon we can see we have made an excellent choice of guide. In line with our shared Hispanic culture, we use the first minutes to ask each other all sorts of personal questions, and after that we are on very friendly terms and it feels more like travelling with a friend, rather than a guide.

The road to the lagoon snakes through immense landscapes, all the time seeing the grandness of the Licancabur volcano in the background. The volcano borders Chile and Bolivia, and it has been worshipped for thousands of years by the Atacameños, the original inhabitants of this land (in local language, Licancabur means ‘mountain of the country’). No matter where you are in the area, it is always within sight, so it makes sense that so much revolves around it, from burying the dead facing the volcano, to legends of gold, human sacrifices and fertility rituals.

Our first stop is Piedras Rojas (red stones), a saline lagoon surrounded by red volcanic rocks. The lagoon’s water is so clear, and the sand is so white, it could be a tropical beach. We move slowly, to avoid losing our breath, and we can feel the altitude. Marvelled, we just stare at our surroundings, and the contrast between the red rocks, light blue water, clear sand and the blue sky. The mountains around the lagoon are coloured in shades of grey, and they seem to have been painted with a thick brush.

Next, we go to the Miscanti and Miñiques lakes, which are right next to each other. Unlike the previous lake, this time the water has a deep blue colour and we cannot see the bottom of the lakes. The full splendour of the Andean mountain range is within sight, brown mountains with snowed peaks. They have a special energy emanating from them, and I feel I can understand the mysticism and veneration these mountains generated in the indigenous inhabitants.

Then we visit the Laguna Chaxa (Chaxa lagoon), which has a healthy population of Andean flamingos. They are relatively common in some natural parks in Southern Spain, but this is my first chance to see them up close. I try to get closer without disturbing them, so focused on the birds that I start sinking on the mud. As I try to get out to drier land, not without having sank my shoes in deep, slimy mud, Guille doesn’t miss the chance to record a video of my struggle, which is quickly sent to all our friends back home.

Our final stop is the town of Toconao, with a small and pretty colonial church. I am just amazed the Spanish came all this way (clearly without the right shoes and altitude sickness medication) and built it. The building seems oddly out of place and right at home, both at the same time. Like it clearly doesn’t belong in this landscape, but it has been built to be part of it.

We use the evening to walk around San Pedro de Atacama and finish arranging our trip to Bolivia. The crossing takes around 3 days, and we did lots of research in order find a reliable driver, as stories of accidents abound. We are very lucky to speak Spanish, as it makes the negotiations easier, and we also have more drivers available, as only a limited number of them speak English. We decide on World White Travel, as it has the best reviews.

The following day we wake up very early to see the Tatio geysers at dawn. We run into many cars driving up the mountain, and once there, we all just wait for the land to erupt. It is quite a magical sight to see it at sunrise, but I am just frozen, and I don’t deal with cold weather very well. As soon as the sun is out it gets much warmer, and we even have the chance to swim in the hot springs. On our way down we stop in Machuca, a traditional village of few mud houses and (of course) a church. They are famous for selling llama meat, but we don’t stay for long. We say goodbye to Zahel, as he will not be coming with us to Bolivia. He has been an amazing, fun guide, and it’s sad to see him go.

Part 2 – Bolivia, Salar de Uyuni

This is the morning of our crossing into Bolivia, and we are very excited. Bolivia has been in our bucket list for a very long time, and it feels like a dream come true. First, we all need to queue to get our Bolivian visas. We queue next to dozens of other tourists (mostly European and South American), and everyone seems as excited as we are. Once the passports are sorted, we meet our driver, Felix. He is very friendly and as we will see in the coming days, a very skilled and professional driver. We will be travelling with 2 other jeeps, and each jeep fits 6 people plus the driver. In our car we are joined by two very friendly couples, French and British. Guille and I are the only Spanish speakers, which has great advantages, like getting Felix to play the music we like most of the trip. While we wait to get going, we listen to the drivers speak to each other in Quechua. Somehow, I was expecting the language of such a barren landscape to be tougher, but Quechua sounds delicate and elegant. To this day, I consider it the most beautiful language I have ever heard.

As soon as we cross into Bolivian territory, the landscape becomes more desolate, more expansive and more spectacular. When you travel a lot, at some point you worry you will lose your capacity of amazement, but Bolivia shows us that this is clearly not the case. No picture can show the beauty of this scenery, the immensity, the colour combinations. When the lakes reflect the sky and the clouds, we feel so close to the sky we could touch it.

I ask Felix to play Los Kjarkas, one of my favourite music bands. They are huge in Bolivia and sing all the classic Andean songs plus their own compositions. As soon as the music starts playing on the radio, it all makes sense. The melancholy of the lyrics and the melodies, the sadness. It all belongs here, in this scenery. I am weirdly transported back to my childhood, and it all feels very familiar. It is strange that these songs, that by now feel like something very intimate and personal to me, belong to this place that I had never visited before. I was meant to come here, I guess.

We make our first stops at the white and green lagoons that border the Licancabur volcano and visit the Geyser Sol de Mañana (morning sun), reaching 4,980m over sea level. We don’t feel altitude sickness but definitely the shortness of breath. One of the drivers offers us coca leaves, which from now on become our oxygen, both literally and metaphorically. Coca leaves have a wide range of properties, from helping with altitude sickness (‘soroche’, as they call it in the Andes) to relieving hunger and fatigue. We take a chunk of them, place them one side of our mouths and slowly chew them. Indigenous people from the Andes have used them for generations, and Bolivia’s former president, Evo Morales, who used to be a coca farmer, made its defense a cornerstone of its presidency.

Our accommodation is a very simple hostel in Huayllajara. There are no showers, and we have to share our room with the French couple. The town is made up of 4 shops plus our hostel. It’s very windy and a bit desolate but has an amazing asset – it’s next to the Laguna Colorada (red lagoon), a spectacular lagoon that is home to thousands and thousands of flamingos. The red of the soil and water contrasts with the blue sky, the grey mountains with snow peaks, and green from the little vegetation that has managed to grow here. It’s like a colour palette. At some point we see a motorist that is crossing the mountains by himself. He is clearly a tourist and I feel like running after him and asking him what he is doing here, how does he cope with the loneliness of the landscape.

Back in our hostel, I stand alone outside, contemplating the nothingness. The wind is blowing strong, and there are barely any signs of human habitation as far as the eye can see. It reminds me of movies I have seen of the Argentinian Patagonia. After a warm and abundant dinner, we go to sleep. I am used to very basic accommodation, but not in cold weather. Nevertheless, after covering myself in layers and layers I manage to sleep very well. Also, what we are seeing is so spectacular and unique, we could continue living in these conditions for weeks on end.

The next day we continue towards the Siloli desert, where the rocks have taken surprising shapes, from camels to trees. I sit next to Felix, so I can monopolise the music (yes, more Kjarkas. I am not sure the rest of the jeep appreciates it as much as me) and also talk to him. A song named ‘Bolivia’ plays on the radio. It talks about Bolivia’s independence and freedom, after the ‘humiliation of the occupation’, and Felix and I started talking about the Spanish. He says he likes us, as we tend to be the friendliest tourists. He is very curious about life in Spain, as he, like most of the country, knows fellow Bolivians who emigrated there. Felix is keen on telling me about the terrible things that happened during times of the colony, like the story of the Potosí mines, but does not blame us, rather wants us to know what happened.

I have travelled around Central and South America, and overall people have been incredibly friendly and polite when they find out I am Spanish (everyone can tell pretty quickly by my accent). There are always some snarky comments, especially when we visit museums or ruins of pre-Hispanic empires, and my ancestor’s hand in eliminating entire communities and cultures is mentioned. The impact of Spanish colonisation has always saddened me, but in the context of the world at that time, I don’t feel particularly responsible or guilty as an individual (and no one has made me feel like I should). Except in Bolivia. The oppression of its indigenous population seems very recent, the pain seems much deeper. I feel very uncomfortable and sad about what my ancestors did, even when everyone we meet is actually very courteous and keeps repeating it is not our fault, we are a new generation, and they don’t blame us, echoing Felix’s words. The country where the wound is still open shows us its kindness. An intense sorrow invades me every time I think about it, even now.

He also talks about Evo Morales, the first indigenous leader the country has ever had. Evo has played a huge role fighting for indigenous’ rights and making people proud of their heritage. I have to admit that in Spain we know him mainly due to his efforts to nationalise Spanish companies in Bolivia, and I was not aware of the huge impact he has had on the dignity of his people. In the coming days we will keep hearing his name coming up again and again, repeating stories of empowerment and advancement.

We drive on to visit more lagoons, and in one of the canyons we see the king of the Andes, the condor. He is very far away but close enough for us to appreciate his majesty, that has inspired many local folk songs. The landscape changes, and from barren canyons we move on to greener plains where the llamas and vicuñas graze. We drive past some small towns, and there is always someone asking us to pay a toll. In one of them that person is a guy who looks indigenous Bolivian but has a very strong Spanish accent. Guille and I are in shock and then it’s too late to ask him about his story.

The landscape changes again, and now we are in a salt flat. There is a train track crossing it, transporting goods from Chile to Bolivia and viceversa. I had never seen a train in the middle of the most absolute nowhere. I don’t think the train passes by very often as Felix encourages us to take a picture lying on the tracks – which we do. That night we are sleeping in a hotel made of salt, Hotel de Sal, which luckily has running water. It has only been one day not showering but feels like weeks, and we are very excited for the freezing water.

The following morning, we wake up before dawn for the highlight of the trip, the Salar de Uyuni, one of the world’s most famous salt flats and the largest one. At the moment it is covered in water, and when the sun comes out, it reflects on it like a mirror. You see everything double, it’s surreal. It is a magical place, a vast expanse of salted surface. It is no surprise then that it is a place of legends (Aymaras believe the salt is milk from the breast of a beautiful woman whose child died), as well as filming location for Hollywood movies. After the first breath stopping minutes admiring the world’s largest mirror, and as soon as the sun comes out, the whole jeep gets into action – like most tourists, we want to take a few pictures that play with the optical illusions of such a flat expanse. Felix has lots of experience on this and gives us very specific instructions – we build human towers, pretend to jump into plastic cups and carry each other. After a bit we are surrounded by tourists, and we realise how lucky we have been to come so early and have the salar to ourselves.

The final stop is the train cemetery, which is exactly that. A few abandoned trains in the middle of a vast expanse of nothing. Even the trains look lonely here.

Part 3 – Bolivia, Sucre

We arrive to the town of Uyuni and look for transportation to our next destination, Sucre. The bus has left so we will have to take a taxi to Potosi and from there to Sucre. Our first driver is Don Jorge Flores, former headmaster of a local school and literature teacher. Talking to him is a real privilege, the conversation is fascinating and very enlightening. He is Aymara, one of the main indigenous groups of Bolivia. As we cross a landscape of arid mountains, he tells us about the sadness the Aymara carry, for the suffering and injustice their ancestors had to endure. As everyone we meet in Bolivia, he doesn’t blame us, but wants us to know what happened. He tells us about the mines of Potosí, which for decades sustained the growth of the Spanish empire and made the city one of the largest ones in South America at the time. The mine in Cerro Rico (rich hill) had huge reserves of silver, which were taken all the way back to Europe to finance Spain’s wars and enterprises. The Spaniards made the indigenous work in the mines without being allowed to leave them for weeks on end; once they started dying, they brought slaves from Africa to replace them. To this day the descendants of the Africans live in Bolivia, mainly in an area called Los Yungas, a humid, jungle like area. Don Jorge narrates these stories with so much sadness in his voice. Guille and I try to accompany him in his sorrow, but there is not much we can say. We were aware of the history of Potosí, but it is not the same reading about it in a schoolbook than hearing the story from a descendant of the workers of the mine. His children all went to university, two of them in Spain, and are now doctors in Santa Cruz and La Paz. He couldn’t be prouder of them and how the country now has opportunities for people of indigenous descent.

As soon as we arrive to Potosí, we can smell the mine. It is unavoidable, a big mountain of black sediment in the middle of the town. As we cross the entrance into the town, marked by an arch, I get goose bumps. I can feel lots of people have died and suffered here. We stop to take pictures, and Don Jorge says, ‘my poor ancestors, they must have suffered so much’. We can only share the sadness. He says he just hopes that Spanish companies will contribute to the development of Bolivia. We hope so too.

Don Jorge makes sure that we find a good, shared taxi to Sucre, and we say goodbye to him, thanking him for sharing so much. Meeting him has been a deeply moving experience. The next driver is very young and plays us bachata in the taxi, so with Romeo Santos in the background we make way to Sucre.

I wanted to stay in Potosí, and also visit another mining town, Oruro, but on this occasion, there is no time. Yet one more thing for our next visit. One of the main attractions of Potosí turns out to be to visit the mine, and you can even throw a pack of dynamite yourself. It sounds an incredibly unsafe thing to do, but also tempting.

In Sucre we are staying in Parador Santa María la Real, a beautiful old colonial building with big, comfortable rooms. After the past days, we cannot wait for a hot shower and a big bed. The owner is the Spanish consul in Sucre, and although he is Bolivian by nationality, he seems to be a direct descendant of the Spanish. As he shows us the building and showcases its history, he tells us Juan Carlos I, the former King of Spain, said Sucre was more Spanish than any Spanish town. As we wander around its pretty streets, Sucre’s churches and the low, white, houses with patios inside, remind us of my native Andalucía. I have never been anywhere further away from home that looked just like home.

We arrive to the cemetery, and I note that everyone’s names and surnames are Spanish, there are only 2 or 3 that sound native Bolivian. How terrible is it that we eliminated their names, such an important part of someone’s identity and memories? Indigenous Bolivians have kept their language, their attires and some of their traditions, but they have lost their names. Names that have been driven into oblivion. I think how important to me is my name, what my surnames say about me and my ancestry, how they help me remember who I am and tell the world about it, and I feel the horror of what has happened here. In Sucre it is a bit easier to digest as many people look Spanish, so their names genuinely reflect part of their ancestry, but how does a Quechua from the highlands end up with a Spanish name and surname? How could we change the identity of an entire continent?

Coincidentally, we are invited to attend a party in a nearby town, Tarabuco. The locals celebrate that they killed a number of Spanish soldiers and ate their hearts. It is actually quite funny how this lives together with the extreme Spanish-ness of Sucre. We cannot go as we are leaving for La Paz the following day, so we enjoy the quietness of this beautiful town, sitting in cafes overlooking the city while we sip coconut milk drinks.

Part 4 – Bolivia, La Paz

To make the most of our limited time in the country, we fly to La Paz, instead of going by road. We fly with Boliviana de Aviación which is a pleasant surprise, both for its punctuality, the service and even the food. The entrance to the city is one of the most spectacular sights I have seen in my entire life – the city was initially built at the bottom of the valley, but it has been growing up the mountains and now it’s just saturated with houses built precariously anywhere where there is a bit of space. The lower part of the city has a milder, warmer climate. The upper parts, known as El Alto (the high), are much colder, and the poorer people, many of them immigrants from rural areas, live there. Legend has it that the Spanish colonisers betrayed an indigenous chief, and when he was dying, he said to them ‘I will come back, and we will be thousands’, and these thousands are now the inhabitants of El Alto. Our driver tells us all this, and then he starts complaining about Evo Morales. He is not happy that he is trying to change the constitution to stay president forever, and says he is also worried about a perceived reduction in the freedom of press in the country.

In my opinion, La Paz is not particularly pretty, although I find the city centre, with its colonial architecture, quite beautiful. Instead, I find the city irresistibly charming in a strange way. It’s kind of grey, but also impressively surrounded by the beautiful Andes. It is raw and the indigenous heritage is alive and present everywhere. I completely fall for it and really enjoy walking around its lively streets.

For our first night we have decided to massively treat ourselves, and stay at Atix Hotel, a new 5-star hotel in a quiet area of the city, which has been chosen by Guille, a hotel connoisseur. It has amazing views, a bar with a pool in the rooftop, and a fantastic restaurant with innovative Bolivian cuisine. Given the global hype around food from neighbouring Peru, we are excited to taste what the chef has prepared for us.

Before that we visit the Valle de la Luna (moon valley), which is a lava field, where you feel like you are walking on the moon. Our driver, also Aymara, speaks very limited Spanish. He tells us that he wasn’t allowed to go to school so he couldn’t learn Spanish properly. He is from a town near La Paz, and moved to the big city so his children didn’t have to ‘dig the land’ like him. He got a loan from the government and was able to send his children to a good private school and now they are doctors. He says before, indigenous people were just ‘surviving’. Now they can also enjoy life, and thanks Evo Morales for all this, and especially for giving them their indigenous pride back. Once again, we thank him for sharing such an emotional and honest story. We feel privileged to hear everyone’s opinions and views, as it adds a completely new dimension to the trip. Given our country’s legacy in the country, we keep waiting for someone to be rude to us, but it just never happens.

For dinner, we have a feast at Ona, the hotel’s restaurant. The dishes are all made with local ingredients from Bolivia, from Amazonian fish to quinoa, Andean potatoes and herbs. It’s delicious and beautifully presented. As we finish the dessert, Guille and I agree that we both hope Bolivian food will start getting more recognition in the years to come.

The next day we are moving to a hotel in the centre of La Paz, Hotel Boutique el Consulado. As its name states, it’s a former consulate (Panamá), and the rooms are spacious and elegant, as well as slightly decadent. We are given a touristic brochure with the main landmarks in the city – it has been put together by the council but sponsored by the Spanish government. It is not the first and will not be the last time that a Spanish public or private entity is behind the preservation of the Bolivian heritage, which is ironic but also makes sense at the same time.

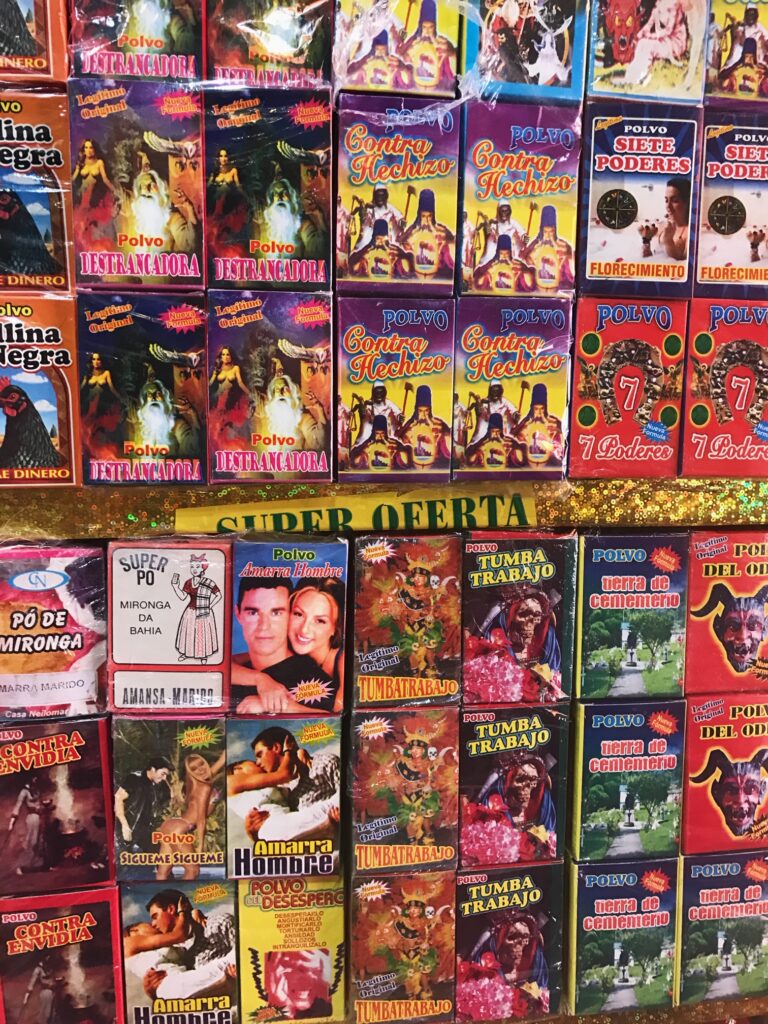

Unfortunately, Guille is not feeling very well, so after making sure he gets a good dose of coca tea, I leave to wander the witches’ market by myself. El Mercado de las Brujas is a collection of shops selling traditional healing remedies, from little statues to offer to the Pachamama (mother earth) to llama foetuses to bury when you build a new house (brings luck) to magic powder to attract men and success at work. It might have had a different purpose before, but nowadays it seems like it is mainly done to attract tourists. I ask for the meaning of the same object in different shops, and every time I get a different answer. Nevertheless, I still find all these objects fascinating, and I resign myself to being slightly ripped off. I buy a few little statues with different purposes – to make sure I continue travelling a lot (which has worked way too well) and to meet a life partner (which has not worked at all). I guess the Pachamama has her own criteria of what is good for me.

When Guille joins me again, later in the day, we walk around the historical centre. We wanted to visit the cathedral, but it’s closed, as there are demonstrations to ask Chile to give Bolivia access to the ocean. The streets are full of children singing and dancing. We visit the Ethnography Museum, which becomes one of my favourite museums of all times. It has a great collection of all sorts of interesting facts about Bolivia’s history and folklore. There is a detailed exhibition about its mining industry, with a big focus on the living conditions of the miners (pretty bad) and folklore around it. There is even a real ‘Tío’ effigy. The ‘Tío’ (uncle) is considered a deity of the underworld in Cerro Rico, Potosí. It dates to pre-Hispanic times, and it offers miners both protection and destruction. There are images of the Tío in mines around the country, sometimes with a more human appearance, other times like a goat. Miners leave offerings such as cigarettes, alcohol and coca leaves. Its effigy is quite scary, but we just cannot stop looking.

There is also a fabulous exhibition on carnival attires from all around the country. The masks and dresses are incredibly beautiful, and quite varied depending on the place of the country – i.e., the ones from the Amazon have feathers of jungle birds. The masks also represent newcomers to the country, from the black slaves to the Spanish, which are easily recognised by their large noses (from a personal perspective, I can understand why). I make a mental note to add Bolivia’s carnivals to my bucket list.

Next, we take the ‘mi teleférico’, the cable car, which goes from the bottom of the valley to El Alto. We love every minute of it, as it allows us to view La Paz in all its splendour. The colonial city centre, the red brick houses in the steep mountain looking like they are about to fall, the flashy, newly built houses in El Alto mixed with more brick houses and the Andes, majestic and dignified. When they hear our foreign accent, other passengers of the cable car are happy to volunteer all sorts of information about it and our itinerary.

In the evening, we go to Calle Jaén, which like its name, looks exactly like an Andalusian street. It is known for its live music, as well as the fact that it is supposed to be La Paz’s most haunted street – ghosts, gnomes and other supernatural creatures. I am really looking forward to listening to live folk music, but unfortunately the bands only play on weekends, and it seems like the ghosts too.

Part 5 – Bolivia, Isla del Sol

We are now heading to our final destination in Bolivia, Isla del Sol (Sun Island), in Lake Titicaca, where legend says the Inca sun god, Inti, was born. The best way we find to get there is with a tourist bus, and it is a bit weird to suddenly be surrounded by dozens of other backpackers. The journey there is a good refresh of my usual Indonesian adventures – bus plus ferry plus bus plus boat plus hike. A bit exhausting but beautiful at all times. The final boat leaves from the aptly named Copacabana, a tourist transit town full of backpackers selling bracelets and drinking coca tea and beer.

We are staying at Palla Khasa Ecological Hotel, which is quite a hike from the port but well worth it. The owner, Don Valentín, sends a donkey to wait for us and carry our luggage, which turns out to be a great idea as we have to go up a steep set of stairs, and we shouldn’t forget we are still around 4,000m over sea level. We have a big cabin all for ourselves with amazing views over the lake, and a big old heater that seems a health and safety hazard. The restaurant also has fantastic views, and we sit there chatting to Don Valentín for hours on end.

Don Valentín is Aymara and a member of the Yumani community in the island. Spanish doesn’t seem to be his first language, and he spoke it mainly when he moved to La Paz for a few years, to work as a builder in El Alto. He then moved back and started the hotel. He tells us the funding for the community comes mainly from tourists and bank loans, and it is then administrated by the council so it can help schools, health centres etc. This local council, where men and women are equally represented, meets once a month.

The next day we hike around the island and end up truly exhausted. We walk for hours, and the landscape reminds us of Mediterranean beaches combined with Inca ruins. There are a few, badly preserved, information panels (funnily enough, also sponsored by a Spanish company), with texts from Spanish priests about life in the island before the arrival of the colonisers. We even run into some stones that were used for human sacrifices during Inca times.

Back in the hotel, don Valentín tells us that the island, other than the birthplace of gods, is also known for its energy. There are two main energy points, one in a mountain and another one in a well in some Inca ruins. Local people go there to pray and make offerings to the Pachamama, and afterwards they can feel positive energy in themselves. Don Valentín also confirms that under the hostel and many houses around the island, there are llama foetuses, just like the ones I saw in La Paz. My favourite story is that apparently there is an elf that tends to appear next to our cabin. My smile freezes when he adds that elves in the island are seen as a sign of bad luck and evil, and that sometimes they are warning of deaths in the community. Thank God the local elf has not been seen in a while.

In the morning it’s raining, and we have to walk back to the port under a torrential rain. Thankfully as soon as we get to the port it stops, and our boat trip back to Copacabana is quite uneventful. In Copacabana we wait for a few hours for our bus to Peru, as we are crossing that same evening, on our way to Cuzco. Both Guille and me are quite sad. Bolivia has been an extraordinary journey and even better than we could have ever expected. The landscapes are spectacular, but it has been the warmth of its people which has had the biggest impact on our trip, and having so many people share their life experiences with us. It has been a real privilege, and it has definitely given a new dimension to our perspective as the descendants of a colonising country. Bolivia has reached very deeply inside me, to parts of my soul that I didn’t even know existed, that are able to feel the sadness of other people who mourn their lost traditions, their dead and even their names.

Note: the names of anyone giving political opinions have been omitted

Arranging the trip:

- Hotels: We booked everything through Booking.com (Bolivia and Valparaiso) and Airbnb (Santiago de Chile and Atacama)

- Flying: We booked our flight directly with Boliviana de Aviación

- Bus: We used Bolivia Hop, booking it online https://www.boliviahop.com

- Getting around: In Santiago we used Uber (Cabify is also available), in Bolivia, local taxi drivers (Uber is operating in La Paz now)

- Atacama guide: Zahel can be reached on +56 9999 96584 or his website http://www.atacamatravesias.cl. He can organise trips in Chile, Bolivia and Argentina

- Uyuni jeep tour: We booked in advance with World White Travel, and then paid in their office in Atacama. I recommend booking in advance for those who need English speaking drivers, as there are not many of them

IMMERSE YOURSELF

- Books to read

- Si esta calle fuera la mía, Stefanie Kremser (Bolivia features in some sections of the book, which is only available in German, Spanish and Catalan)

- Films to watch

- When the bull cried, Karen Vazquez Guadarrama, Bart Goossens

- Eugenia, Martín Boulocq

- Cerro Rico – The silver mountain, Armin Thalhammer

TIPS

- Women travellers

- I felt very safe at all times, but it was massively influenced by the fact that I am a native Spanish speaker and I was with a male friend at all times. I felt safe wandering around by myself in La Paz and Sucre, but I don’t think Bolivia is the easiest destination for a woman to travel by herself off the beaten track

- Safety

- We felt quite safe but were mindful of our belongings at all times, especially when taking public transportation and walking around central La Paz or El Alto

- I would recommend checking first with your hotel before going to certain places at night, especially in bigger cities and if you don’t speak fluent Spanish

- Weather

- May to October has drier weather and clearer skies, but it can get quite cold, especially at night

- We were there in March and had excellent weather at all times