November/ December 2015

Most of the world does not know West Papua exists. At best, they have heard about its raucous brother to the East, Papua New Guinea (PNG), which evokes images of exotic dances, feather ornaments and unfortunately, violence. Indonesian Papua (which I will refer to as West Papua, despite comprising both the provinces of Papua and West Papua) shares a similar culture to PNG but its paths have diverged due to its political history. It has been hidden from tourism for years, and it is only recently that Raja Ampat, in its westernmost corner, has become a magnet for scuba divers from all around the world. The rest of the region remains a destination for mine workers, Indonesian fortune seekers from other provinces, a few intrepid travellers and, even to this day, Christian missionaries.

Venturing outside the diving hotspot is, even for Indonesian remote travelling standards, hard work. Government permits, unreliable ferries, impossible flight connections with accident prone airlines, hotels that disappear overnight and activities that require all sorts of negotiations with local guides, fishermen and other intermediaries, to only name a few. Those who make it will be rewarded with jaw-dropping, unspoilt landscapes, that range from forests to jungles to beaches, unique endemic species and fascinating cultures that have had very limited western influence. In short, one of humanity’s most precious places.

Despite being part of Indonesia, West Papua is a world apart. Its inhabitants are racially Melanesian (like some of the islands in the South Pacific such as Vanuatu and Fiji), Christian/ animists, and culturally very different. They had very advanced agricultural practices thousands of years ago, sophisticated art techniques, a deep connection to the surrounding environment and, thanks to their relative isolation and the lack of land infrastructure, many areas have remained quite traditional. Many of their customs have been banned, such as tribal infighting, but they still happen every now and then – one of the highlights of my trip was seeing a Tripadvisor review that highlighted a hotel as ‘best place to hide in case of tribal warfare’.

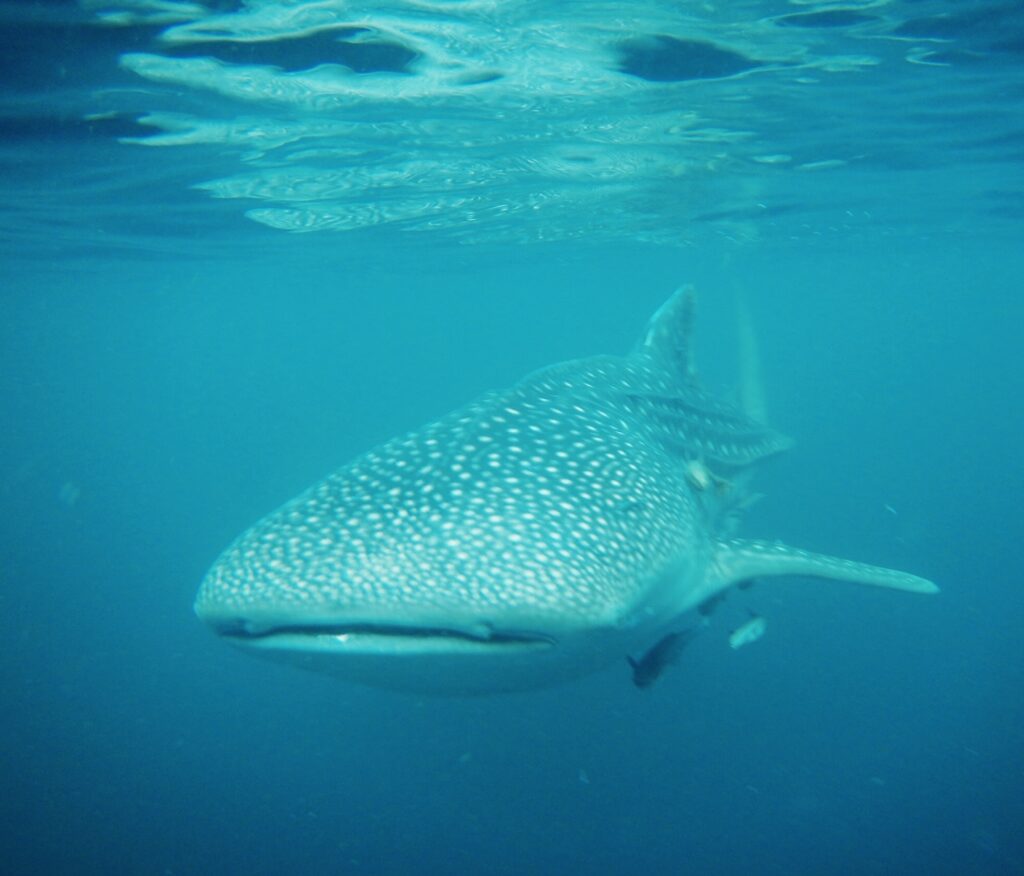

This isolation has also benefitted the local fauna, with the island being home to hundreds of unique bird species, including birds of paradise, and rare animals such as the tree kangaroo. The underwater ecosystem is also beyond par, with colourful coral and many pelagic, including mantas, whale sharks, wobbegong sharks and even the rare epaulette, the walking shark.

Part 1 – Hiking the Baliem Valley

Our trip starts, like all good Indonesian adventures, with a 4am domestic flight, this time from Bali. My cousin Cristina has surprisingly agreed to join me on a trip to a part of the world she probably didn’t even know it existed. Our flight to Jayapura, West Papua’s capital, stops in Timika, the closest airport town to the Grasberg mine, the largest gold mine in the world and the second largest copper mine. Its main shareholder is the American mining company Freeport McMoran, omnipresent in the area. As we leave the plane for a quick stopover the company is everywhere – the airport bus, the seats at the airport and even the toilets have the company’s name.

Onwards to Jayapura the plane flies over miles and miles of green and nothing else. No roads, no buildings, nothing. Just the wilderness. The landing allows us to admire beautiful lake Sentani, but this time we will not have time to stay for long. As soon as we arrive, our guide, Usman, (with whom I negotiated a detailed itinerary weeks before) meets us at the arrivals gate only to take us to departures again. We are flying to Wamena, the capital of the Baliem Valley in the highlands, for a 5-day hike. The queues at the check in desks already show us we are in a different world from Bali – barefoot locals carrying huge bags of potatoes, American Christian missionaries and the odd tourist. I feel the rush of adventure all over my body. After months of planning and sleepless nights, re-doing the itinerary and trying to make flight connections work, we are finally here. A dream come true.

We spend the night at the Baliem Pilamo hotel, preparing for the adventure ahead. It offers basic but clean accommodation and seems to be the preferred choice in town for government officials and tourists alike. In the meanwhile, Usman finds 4 porters plus a cook, Pak Martinus. All of them belong to the Dani people, one of the most populous groups in the highlands and from the same ethnic group of the areas we will be visiting. We need them to help us carry both our bags and the food we buy in Wamena, as the villages where we will be staying have very limited resources.

The journey starts with a short car drive – with the 8 of us plus the driver fitting in it. The car takes us as far as the road goes, to Kurima, and then we start walking. On this first day the path is quite easy, and we only stop to have lunch in a village, where children seem to be used to tourists passing by and they quickly offer to pose for pictures. We continue walking on until we reach Hitugi, where we will be spending our first night. Until now we have walked through a forest, but it is in Hitugi that we see the majesty of the mountains in the Baliem Valley for the first time. Green hills rolling as far as the eye can see, some of them with potato field terraces, where Dani women work, despite the steep terrain. Small hamlets here and there, with thatched huts. And the knowledge that we are entering a very precious and unique world.

Our afternoon is spent visiting some nearby fields and talking to people on the roads – women carrying large heavy net bags (‘noken’) held by gripping their heads, and men naked but for the penis gourd (‘koteka’). They all greet us in Bahasa Indonesia or in the traditional form – holding one of our hands with both hands, shaking it and saying, ‘wah wah wah’. On returning to Hitugi we meet the first and last foreigners we will be encountering during our trek, a group of Germans who live in Jakarta and just arrived from visiting the Korowai, in the south of Papua. The Korowai live in tree houses in the wetlands, and the Germans seem to have been walking on mud for days on end. They also seem quite surprised to see two Spanish girls by themselves.

We will all be staying in traditional huts, made of stone and mud with a thatched roof, sleeping on mats on the floor, which are surprisingly comfortable. It will be the bathing arrangements that will prove problematic for me, as the local bath house (a hut with a pool of water and a bucket) is in the middle of village and has a door that only covers half of my body – quite understandable as at 180 cm / 5.10 ft I am much taller than the average Dani. I will have to wait until everyone is asleep and have a midnight shower, the first of many.

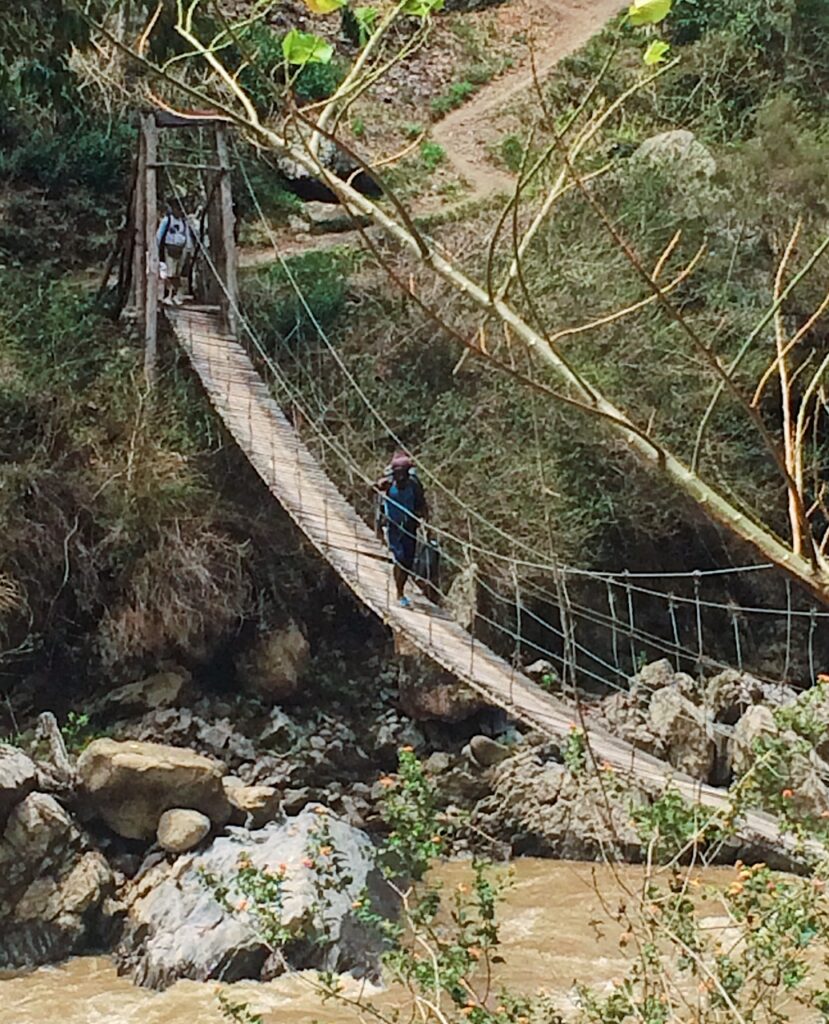

Our next stop is Yuarima, and we will have to cross a rope bridge across the river to get there. The bridge doesn’t seem too stable, and they ask us to cross it one by one and very carefully. The Danis don’t seem to be too faced by it, crossing it quickly, with flip flops and heavy loads and children on their backs. For us it seems quite a feat, and we promptly clap our hands whenever a European manages to cross it successfully. We part ways with the Germans, who are doing a shorter itinerary, and slowly start ascending the mountains. The landscape changes from fields to tall trees and dense forest, always with the river by our side.

Yuarima is more traditional than the villages we have previously seen. It is here that we first see some elders with amputated fingers. I had read about this fascinating practice in Norman Lewis’ book, ‘An empire of the east’, and I was eager to learn if it was still taking place. It is a Dani tradition to cut the upper part of a finger as a way of showing grief and mourn the dead of a relative. Based on the intensity of the grief, more than one finger can be amputated, up to 6, and afterwards the upper part of the ears can be cut as well. This practice has been banned by the Indonesian government, but it seems to still be happening in some of the more remote areas. Yuarima is also poorer, and its isolation means that medical care is limited. A number of the older people seem to suffer from ailments, but we are told the doctor can only visit every few weeks. They ask us for help, but we are not carrying much more than eye drops and ibuprofen. Nevertheless, our hosts are unfailingly polite and friendly, like everyone we meet in the Baliem Valley, and are happy to just sit in silence with us.

We were planning to hike even further, to Syokosimo, but I have sprained my ankle and need help from our porters to walk every time the terrain gets steep, so we decide to go straight to Kilise. We continue crossing beautiful, lush green hills, stopping every few hours to savour Pak Martinus’ delicious nasi goreng (friend rice), one of the best I have ever tasted in Indonesia. We meet people that are walking 3 to 4 days just to get to Wamena and sell their goods in the market. They all want to stop and chat, ask about where are we from, if we are married and what are we doing there. By now I have learnt by heart the Indonesian word for tall, ‘tinggi’. Children scream it when I walk by and the elders enjoy having a proper discussion about it.

By the time we get to Kilise our hosts present us with a very strange welcome gift – a collection of German football t-shirts. After a few minutes of confusion, we understand what happened. The Germans, who are a day ahead of us, wanted to give them the t-shirts, but were too embarrassed to just offer them directly so they left them under the sleeping mats instead. We have to explain to the family that it is theirs to keep.

On our final day we walk back to Kurima. The road is crowded with Danis going to the Wamena market, and I photograph an elder dressed in traditional clothes (koteka and crown made of leaves) that seems to have the honour of being the most photographed person in West Papua. I am pretty sure I have seen him in dozens of pictures available on the internet, a theory which is further reinforced when he asks me for money in exchange for taking the picture.

Once we reach Wamena, and given we have an extra night, we decide to stay in a traditional village close to town, Obia, to see traditional dances. It is clearly done for the benefit of tourists, which tends to put me off, but we decide it is ok as we are the only ones around anyway and it doesn’t make it any less interesting. The men wear kotekas, head ornaments made of bird of paradise feathers and tusks in their nose. With spears in hand, they enact traditional fights and dances. Then the women, also wearing traditional attires, grass skirts, dance and sing, and display a number of traditional artefacts as souvenirs. You can buy anything from kotekas, pumpkins to carry water, net bags and even the stone used to cut fingers.

Part 2 – Jayapura and Nabire

On our return to Jayapura, we take time to visit the local museum, which comes very highly recommended (once again, the Germans are ahead of us). The museum has a very knowledgeable curator and a comprehensive collection of local art, especially from the Asmat region in the south, known for the beauty of its carvings. It was in that part of West Papua that Michael Rockefeller disappeared in the early 60s while he was exploring the area. To this day there is still speculation over if he was eaten by cannibals or by a saltwater crocodile. Like everything in West Papua, we take it as it is. Everything seems possible here.

Jayapura is also our chance to try the local cuisine – eating in one of the restaurants by the lake Sentani, which offer beautiful views and delicious local fish spiced up with Indonesian sambal and tasting sago soup in the local market. The sago, a starch extracted from the centre of tropical palm trees, is a staple food in the island of New Guinea and many Pacific islands, and I have to admit I am quite a fan of its gelatinous texture.

After a day of ‘rest’, we feel ready for the next adventure – our guide has suggested that we cross into the Papua New Guinea border, only a few hours away from Jayapura. People cross it every day to trade goods and Usman seems to think they will let us in easily. We decide it is a great idea and go for it, only to arrive and be told by the customs police that they cannot do our visa and we have to go to Port Moresby if we want to enter the country. After seeing my disappointed face, they kindly agree to let me put my feet on the border and have my picture taken. I get itchy feet just to think of the adventures that await on the other side. Nevertheless, the landscape between Jayapura and the border is very green and beautiful, combining both tropical and highland trees, and it is a day well spent. We also get to see a few transmigration villages on the side of the road. The ‘transmigrasi’ policy, by which population from massively populated Java moved to less populated areas of the country, such as West Papua or Kalimantan, was started by the Dutch and continued by post-independence Indonesian governments. It reached its peak in the 80s and was officially put to an end by President Jokowi in 2015 but has left semi-abandoned Javanese looking villages in the most unexpected corners of the Indonesian archipelago.

Our next stop is Nabire, famous for its whale shark sightings, as they follow local fishermen when they retrieve their nets, hoping to share the catch, and can be spotted on a daily basis. There is one resort that offers diving/snorkel packages at exorbitant prices, and refusing to contribute to the local monopoly, I decide we are going to arrange our own dive. We stay at Hotel Getz, in the centre of town, and the friendly owners help us arrange a visit to the whale sharks for the following day through a local fisherman. In the meanwhile, one of the owners’ friends, Michael, who moved here with his family from Manado, Sulawesi, offers to take us around Nabire and its surroundings. We arrive to a sleepy pier with a few local families taking selfies and start consuming all the fruit we bought on the side of the road on our way there – soft durian that almost melts in your mouth, dry but tasty snake fruit and juicy rambutan.

The following day, the fisherman never shows up and our new friend offers to drive us to the whale shark diving spot. It starts raining heavily and the roads get flooded, so the journey takes hours and hours (especially on the way back where the driver has to swim through parts of the road in order to get the car to move). Never mind – every single hour on the road, every bump, every challenge. It is all worth it once we see the sharks. A tiny boat drops us with our snorkeling gear next to one of the fishermen’s boats and there they are, as soon as we jump into the water. They are one of the most beautiful, majestic creatures I have ever seen in my life. They are breath-taking. We just stay there, swimming and floating and admiring them while they feed and swim around. The sharks feed by absorbing large quantities of plankton and small fish, reminding me of a hoover. They also seem to be quite curious about us and get quite close, as I feel something bumping against me and I turn around to see one of the sharks. They are huge (on average 3 times my height), but yet so inoffensive and delicate. We feel hugely privileged to enjoy these moments alone with them, and they almost have to drag me out of the water so we can go back to Nabire.

Part 3 – Raja Ampat

We return once again to Jayapura, to fly to our final destination, Sorong, the departing point for the dive resorts in Raja Ampat. This time we are treating ourselves and stay at Papua Paradise, an all-inclusive resort for diving maniacs – all you can dive (within safety limits). The resort has beautifully built cabins over the water, with all the amenities but still blending in with the environment – including dugongs that visit our cabin every evening. The food is buffet style but delicious and plentiful and I devour their home-made chocolate donuts after every dive.

The diving is the best I have done in the whole world. The abundance and diversity of the underwater life, the beauty of the corals, the visibility… and Papua Paradise’s Spanish run dive shop is the perfect companion to enjoy it. Julián, the manager, helps us tailor our dives to our interests, and our dive guide, Andy, makes every dive an exploration of the underwater wonders. We do most of our dives with a lovely Canadian couple, Jim and Christine. They travel the world following the diving seasons and take beautiful underwater photos (which have been my phone/ laptop screensavers ever since).

Papua Paradise has some impressive local dives, only a few minutes away, but also offers day trips to some of the most famous diving sites around, such as Kri Island, and the very instagrammeable viewing deck at Pianemo, overlooking the lagoons. We like Kri so much that we go twice. We dive in Melissa’s Garden, the most colourful, stunning coral garden I have ever seen. Corals come in every shape and every colour and you wonder how nature can create something so perfect. The current takes you on a tour (sometimes more like a rollercoaster ride) and you just let it show you the site and focus on admiring your surroundings. My favourite dive is Yenbuba, where you can dive at your own pace next to a wall full of nudibranchs and other macro life, such as pigmy seahorses, and on your left, there is the blue, with a very strong current that attracts all the pelagic from miles around. The current is so strong and full of plankton that the visibility is limited, but for a few seconds you get to see all sorts of creatures, from huge black tip sharks to mantas and dozens of devil rays. It’s like a parade of the sea’s most stunning inhabitants.

Close to the resort lies the main reason that brought me here in the first place – a dive spot that during the right season, acts as a cleaning station for mantas. We ask to be taken there almost every day and never get tired of it. The dive consists of just holding to a rock with all your strength (the reason why it is a cleaning station is because there is a very strong current) and admiring the mantas swimming around you for as long as your air allows you, around an hour. The mantas are elegant and (I have to use this word again), majestic. I just stare in awe and have to remind myself to breathe. They are also very friendly and like to get close to us. As this dive spot is relatively far away from other resorts, it is only us there and a few other divers from Papua Paradise, which is quite rare nowadays in Raja Ampat dive sites.

At night we patrol the local coral reef, and we are lucky that in almost all our night dives we get to see the wobbegong sharks. They are semi-hidden under rock caves, and can get aggressive if you get too close, so we have to observe them from a careful distance. They remind me of an old carpet, covered in whiskers and camouflaging with its surroundings. On a couple occasions we even see the epaulettes, the walking sharks, transporting themselves slowly through the bottom of the sea. After watching BBC’s ‘Shark’ maybe 50 times, I cannot believe I get to see these rare sharks so easily. Raja Ampat is truly a treasure of marine biodiversity, and since 2007 marine protected areas have been created, among other things to prevent sharks being fished for their fins. Contributing to the park’s fees and staying in resorts that contribute to conservation programmes is of utmost importance if we want to continue enjoying this jewel.

Our trip around West Papua comes to an end, but I leave with a long list of pending places I want to visit in the region – Biak island, Manokwari to admire the birds of paradise, Korowai region to see the tree houses… The list of things to see in Papua is endless.

Arranging the trip:

- Flying: Most Indonesian airlines fly to Sorong and Jayapura from Jakarta, Bali Denpasar and Makassar. Some internal flights within West Papua can only be booked at the airport (e.g., Susi Air). Traveloka allows bookings with non-Indonesian credit cards, Garuda Indonesia is often the only Indonesian airline to allow that

- Getting around: Download the transportation apps Go-Jek and Grab, they have both motorbikes and cars and work in most Indonesian cities – Grab even translates into English the messages you get from the drivers and it can be topped up with an international credit card

- Trekking: Guides and porters for the Baliem Valley can be arranged on arrival, but we felt more comfortable doing it in advance. There are a few websites advertising tours, but they can be quite expensive – we talked to quite a few guides and compared prices. Other travellers recommend asking your hotel for reliable guides

- Travel permit: The travel permit around West Papua, the Surat Jalan, can be done at a local police station, guides are able to arrange it

- Hotels: Baliem Pilamo Hotel, Hotel Getz and other accommodation can be booked through Traveloka or Booking.com

- Diving:

- Nabire: You can find local fishermen to take you to see the sharks, we arranged it through our hotel

- Raja Ampat: Papua Paradise (https://www.papuaparadise.com) gets fully booked months in advanced and early booking is recommended

IMMERSE YOURSELF

- Books to read

- An empire of the east: Travels in Indonesia, Norman Lewis

- Into the crocodile nest: A journey inside New Guinea, Benedict Allen

- Throwim way leg, Tim Flannery

- Indonesia, Etc.: Exploring the improbable nation, Elizabeth Pisani

- Four Corners: A Journey into the Heart of Papua New Guinea, Kira Salak (takes place in Papua New Guinea)

- Beyond The Coral Sea: Travels in the Old Empires of the South-West Pacific, Michael Moran (takes place in Papua New Guinea)

- Journeys to the other side of the world: Further adventures of a young David Attenborough, Sir David Attenborough

- Films to watch

- Best documentary TV shows where West Papua features: Blue Planet, Our Planet, Shark and Tales by light (all available on Netflix)

TIPS

- Women travellers

- I felt very safe travelling around West Papua as a woman, everyone was incredibly respectful and made me feel comfortable

- I felt I could dress however I wanted at all times

- Safety

- West Papua is very safe as a whole and we felt at ease for the whole trip. However, it sees social unrest on a regular basis – you should monitor the situation before travelling there (The Jakarta Post is a good resource, also your embassies in Jakarta)

- Some parts of the highlands are seen by the Indonesian army as OPM (Organisasi Papua Merdeka) strongholds – you should avoid going there

- The Surat Jalan is a requirement and should not be taken lightly – the army checked our documents when we passed security controls

- There have been a number of incidents in the past where foreigners who get involved in internal political matters of Indonesia / West Papua have been deported from the country

- Weather

- Climate is quite stable in the highlands all year long. We had mostly good weather and some brief, torrential rain in the evenings

- Diving is best from September to April, and the best months for mantas are October to December

- Other considerations

- Phone connection is very limited around the highlands, even with Telkomsel, which tends to work all around Indonesia

- I recommend carrying cash around the highlands to purchase souvenirs or tip local families who manage tourist accommodations